Many greetings and wishes

Issue #2

Remember that you can also read this blog in spanish.

Art has always been humanity’s most profound way of communicating with itself across time. Through brushstrokes, melodies, and words, we send messages into the future, capturing who we are and who we might become. Some works stand as monumental landmarks in this ongoing dialogue, transcending their creators’ moments to echo across centuries. They contain stories within stories, layers of intention and meaning, technical brilliance, and emotional resonance.

Today, let us explore a collection of such pieces, each with its own unique place in the vast tapestry of human creativity. These works are more than just artifacts; they are vibrant, living entities that continue to provoke thought and feeling.

Let’s begin.

The intakes

The ones that hit the mark.

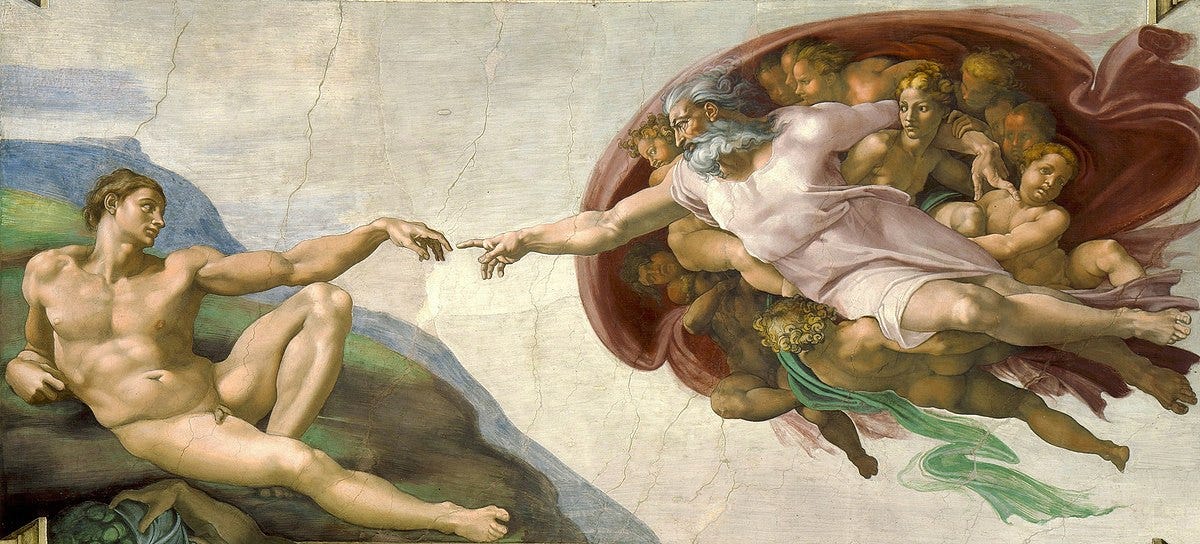

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam is not merely a fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; it is a cornerstone of Western art, a visual metaphor for humanity’s eternal quest for meaning. Painted between 1508 and 1512 as part of a larger commission to decorate the chapel ceiling, this iconic scene stands out for its unparalleled emotional and technical depth. Michelangelo was working under extraordinary pressure, navigating the expectations of Pope Julius II, the physical demands of painting a vast ceiling while lying on his back, and his own perfectionist tendencies. Despite these challenges, he created a work that feels almost divinely inspired.

The composition is both simple and monumental. God, surrounded by a host of angels, reaches out to touch Adam, who reclines languidly on the earth. The near-touch of their fingers is the focal point of the image, charged with a tension that suggests the very moment of creation—the spark of life transferring from the divine to the human. This “gap” has been interpreted in countless ways, symbolizing everything from the distance between humanity and divinity to the perpetual striving for knowledge and enlightenment.

On a technical level, Michelangelo’s understanding of anatomy is nothing short of astonishing. Every muscle in Adam’s body is rendered with a precision that speaks to the artist’s study of cadavers and his obsession with capturing the human form in its most idealized state. Yet, the painting is not just about physicality; it’s about the spiritual and intellectual potential of humanity. Michelangelo’s use of color, light, and shadow enhances this duality, making the fresco both grounded and otherworldly. This is not merely a scene from the Book of Genesis; it is a timeless meditation on the nature of existence.

Melancholy Blues by Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven

Recorded in 1927 by Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven, Melancholy Blues is a jazz standard that encapsulates the spirit of a rapidly changing era. The 1920s were a time of innovation and upheaval, with jazz emerging as a powerful voice for cultural and social transformation. Armstrong, already a towering figure in the genre, brought an unparalleled sense of soul and sophistication to this recording. Written by Marty Bloom and Walter Melrose, the song’s lyrics and melody are steeped in longing, but it is Armstrong’s performance that elevates it into something transcendent.

The piece begins with a mournful piano line, setting a contemplative tone before Armstrong’s gravelly voice enters. His trumpet solos, both restrained and emotionally charged, weave in and out of the arrangement like a conversation with the listener. Each note carries a weight that feels almost tangible, as if Armstrong is pouring his own experiences into the music. The interplay of the brass and rhythm section is a testament to the improvisational brilliance of jazz, with every instrument contributing to the song’s narrative arc.

Historically, Melancholy Blues represents more than just a musical achievement; it is a snapshot of the cultural ferment of the Jazz Age. Armstrong’s work during this period laid the groundwork for countless musicians who followed, redefining what was possible in both jazz and popular music. The song’s themes of loss and resilience resonate across generations, reminding us that even in our darkest moments, there is beauty to be found.

Avril 14th by Aphex Twin

Aphex Twin, the moniker of Richard D. James, is best known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music. Yet, with Avril 14th, released in 2001 as part of the Drukqs album, James took an entirely different direction, creating a simple and hauntingly beautiful piano piece. What many don’t realize is that this composition wasn’t performed by James directly but instead programmed into a Yamaha Disklavier, a computer-controlled piano that translates digital instructions into acoustic sound.

The use of the Disklavier adds a layer of intrigue to Avril 14th. While the music feels deeply human—its hesitant rhythm and uneven dynamics reminiscent of a live performance—it is, in fact, the result of precise programming. This blending of human emotion and machine execution mirrors the duality of James’s work, which often explores the intersection of organic and synthetic. The slightly mechanical imperfections, combined with the piece’s minimalist melody, evoke a sense of nostalgia and impermanence, as if the music is fading even as it plays.

Avril 14th has since become one of Aphex Twin’s most celebrated compositions, used in film scores and covered by countless artists. It serves as a reminder that even in the age of technology, simplicity and emotional resonance remain at the heart of great art.

Ode to Freedom by Leonard Cohen

Leonard Bernstein’s historic performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in December 1989, celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall, stands as a monumental event in music history. Conducted in Berlin’s Schauspielhaus, the concert was broadcast live to over twenty countries, reaching an estimated audience of 100 million people. In a profound gesture, Bernstein altered Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” by substituting “Freude” (joy) with “Freiheit” (freedom), transforming the piece into an “Ode to Freedom.”

This adaptation resonated deeply, symbolizing the newfound liberty and unity following the Wall’s collapse. The performance featured musicians from both East and West Germany, as well as from the United Kingdom, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States, embodying a spirit of international collaboration and hope.

Bernstein’s “Ode to Freedom” not only celebrated a pivotal moment in history but also underscored the enduring power of music to transcend political divides and inspire collective humanity. The concert remains a testament to the role of art in fostering unity and freedom.

The Outtakes

Although they’re cool, I wouldn’t want my son listening to them on repeat.

The Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello

This Renaissance masterpiece is a study in perspective and geometry, capturing a 15th-century Florentine battle with breathtaking precision. But beneath its vibrant colors and intricate composition lies a glorification of war. The painting, commissioned to celebrate a military victory, feels at odds with the introspective and universal themes of the main list. Its focus on violence, even as art, serves as a reminder of the darker impulses that drive human history.

Ode to Sleep by Twenty One Pilots

This genre-defying track is a whirlwind of emotion, oscillating between despair and hope. But its frenetic energy and dark undercurrents felt too jarring compared to the quieter meditations of the primary selections. The song’s themes of mental health struggles, while important, risked overshadowing the broader, more contemplative tone of the list.

You and Whose Army? by Radiohead

I love this piano cover by Distance to Empty

Radiohead’s You and Whose Army? is a haunting critique of power and arrogance, its ethereal vocals and minimalist instrumentation building to a crescendo of defiance. This piano cover strips the song down to its raw emotional core. Recorded with a mix of analog and digital equipment, the imperfections—ambient noise, uneven lighting—enhance its intimacy. Yet, the stark vulnerability of both the original and the cover felt almost too personal, making it difficult to align with the broader, universal tone of this collection.

![Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Battle of San Romano (probably c. 1438–1440), egg tempera with walnut oil and linseed oil on poplar, 182 × 320 cm, National Gallery, London.[2] Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Battle of San Romano (probably c. 1438–1440), egg tempera with walnut oil and linseed oil on poplar, 182 × 320 cm, National Gallery, London.[2]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Zn7l!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe27acd3a-a658-4900-b4df-1c2b09d76e95_2880x1629.jpeg)